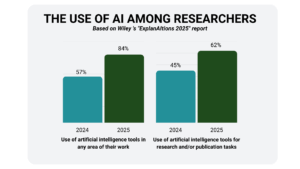

The rise of artificial intelligence has not spared the world of scientific publishing. In recent years, more and more researchers have turned to AI tools for writing, editing, or translating manuscripts. In this blog post, we explore what authors should keep in mind when using AI, how different publishers approach the issue, and what guidelines can help navigate this rapidly changing landscape.

The state of play

In recent years, the role of artificial intelligence (AI) has grown dramatically in many areas of everyday life, so it is not surprising that a growing number of people in the scientific world are turning to AI-based programs for help and using these tools to write, edit, or even brainstorm ideas for academic papers. However, these changing authoring habits pose serious challenges for the academic community and publishers, who are trying to develop appropriate guidelines and rules—with varying degrees of success.

That is why it is particularly important today for researchers and authors to be aware of how and to what extent AI can be used in the preparation of scientific manuscripts, as the inappropriate or non-transparent use of such technologies can easily lead to the rejection or retraction of manuscripts, or even to serious ethical issues.

Our website already features a detailed list of editorial guidelines on AI use, broken down by publisher. In this blog post, however, we would like to present a broader picture: our goal is to provide an easy-to-understand overview of what to look out for when using AI for scientific purposes, regardless of which publisher the author plans to publish their work with.

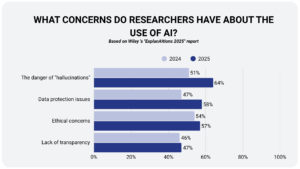

You can read the full report from Wiley HERE.

What do we know for certain?

As mentioned earlier, the academic world is also taking advantage of the opportunities offered by artificial intelligence. As part of this, publishers of scientific journals have formulated various guidelines to regulate the use of AI tools in submitted manuscripts.

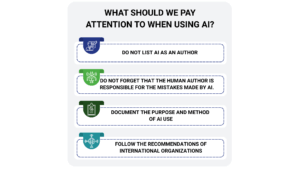

However, authors who try to follow these rules or guidelines do not have a straight-forward path. Each publisher has its own rules, and in some cases, there are even multiple rules within a single publisher, with journal editors formulating their own guidelines. Despite this, there are a few basic principles that appear almost everywhere and that all authors should pay attention to, regardless of where they plan to submit their manuscript.

The first and perhaps most important principle is that AI cannot be listed as an author on the manuscript. The reason for this is that authorship implies responsibility, contribution to the intellectual content of the research, and conscious acceptance of the consequences of publication—all of which artificial intelligence is incapable of fulfilling. Therefore, artificial intelligence, or any service based on it, cannot be listed as a co-author in a work, even if their use was relied upon to a significant extent in the preparation of the manuscript.

Since AI cannot be an author, therefore, the human author is responsible for the entire content of the work. This means that if AI generates incorrect data and the author uses it, the author is liable. This is particularly important given that, although AI models are able to provide increasingly accurate information, so-called “hallucinations” are still present in the generated data. Therefore, it is extremely important to double-check and validate AI-generated content, as a publication containing incorrect data can damage one’s reputation.

Another recurring key issue is transparency. Publishers expect authors to clearly document how and for what purpose they used AI. Some publishers also specify in which part of the publication the use of AI should be indicated, but most publishers do not provide guidance on this. In these cases, it is worth mentioning that AI was used in the methodology section or in the acknowledgements, depending on the purpose for which the software was used. Accurate documentation is important not only from an ethical standpoint, but also from a practical one: it helps editors and readers understand the background of the research and verify its reliability.

When it comes to transparency, it is also worth mentioning the issue of the preciseness of documentation. If we use generative AI, it is advisable to describe not only the purpose of its use, but also the exact process, as the answers provided by AI are often not reproducible due to the so-called black box phenomenon. If we specify the prompt used in our documentation and the reviewers reuse it, it is almost certain that they will receive a response that differs from the original. Therefore, it is worth documenting both the prompt and the response received accurately.

Finally, it is worth paying attention to the recommendations of international organizations (such as COPE or ICMJE), as many publishers base their own guidelines on those of these organizations. In addition, these recommendations can help you navigate when the rules of the chosen journal are not entirely clear.

What are the key differences?

Despite the few principles listed above, the rules governing the use of artificial intelligence in scientific publications are far from uniform, and authors should be aware that differences between publishers can have a significant impact on what is expected of them.

One of the most important things to keep in mind is the constant technological change. Due to the rapid development of the AI world, publishers regularly update their guidelines. What is acceptable today may change tomorrow, so it is always a good idea to check for updates before submitting your manuscript.

Local regulatory practices pose an additional challenge. Many publishers, such as Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, allow each journal to develop its own guidelines rather than applying uniform, general guidelines. This means that even two journals from the same publisher may have completely different expectations regarding the use of AI. It is therefore not enough for authors to know the name of the publisher—they need to know exactly which rules apply to the journal in question.

Documentation requirements also vary. In some cases, a few sentences describing the methodology are sufficient, while in others, a detailed report is required. In some cases, it is even specified exactly where in the text the use of AI should be indicated. As mentioned earlier, it is advisable to document the use of AI as accurately as possible, as expectations in this regard may vary.

Finally, there are smaller or independent journals that do not have an official position on the use of AI. In such cases, it is recommended that authors follow the principle of transparency or, if they have any questions, contact the editorial office of the journal.

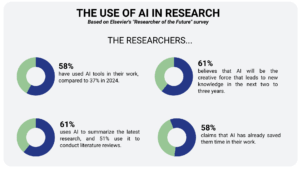

You can read the report on Elsevier’s survey HERE.

How do they monitor the use of AI?

As AI tools become increasingly popular among researchers, publishers are introducing tools that attempt to filter out covert AI use. These so-called AI detectors (such as GPTZero, Turnitin’s AI detector, or tools developed internally by some publishers) automatically analyse text and attempt to determine whether it was generated using artificial intelligence.

These software programs work on the basis of certain linguistic patterns: they use statistical models to analyse the structure of the text, word usage, sentence length, repetitions, and text coherence, and compare the results with text characteristics frequently used by AI. In fact, these detectors do not check whether the text was written by AI, but whether the text resembles texts created by generative artificial intelligence. However, this verification method can cause serious problems for authors.

Authors who write their articles in a foreign language may fall victim to such detectors. In such cases, people tend to use familiar and well-established expressions or simpler sentence structures, but these are often mistakenly detected by the systems as being AI-generated. Similar misunderstandings can also occur in very narrow fields of science, where technical jargon consists of repetitive formulas.

This is why it is important for authors to clearly indicate when they have used AI, even if they have only used programs for translating or grammatically correcting the text, as this will prevent the system from “catching” them for a use that they would otherwise openly admit to.

If a dispute does arise, it may help to be able to show the earlier stages of the writing process. Simple version tracking (e.g., Word’s “Track Changes” feature) or early drafts of the manuscript can serve as evidence that the text is indeed the result of human work.

You can read the full report from Wiley HERE.

What is allowed?

Many may ask: with so many restrictions, what can we freely use from the artificial intelligence toolbox? The good news is that most publishers differentiate between generative AI and assistive AI tools.

We have already mentioned the most important points regarding generative AI (such as checking generated content and the importance of documentation), but the use of assistive AI is more acceptable to publishers, as it does not involve content generation, but rather auxiliary functions.

The use of spell checkers and grammar checkers is generally not a problem, especially when the goal is to improve the clarity and readability of the text. Similarly, translation programs that use AI are also widely accepted and can be a huge help for authors who are not native English speakers. However, it is important that authors always check the accuracy of the translation and correct the text if necessary.

Similarly, publishers accept the use of artificial intelligence-based manuscript editing software, such as Paperpal, which is also available at the university, as these are again support functions.

More and more reference management software, such as Zotero and EndNote, also offer AI-based features that help organize and format references. These are, of course, also accepted, as the actual author of the text is still a human being.

As with generative tools, it is important to clearly communicate how these tools are used. Since expectations may vary from publisher to publisher, it is worth checking the guidelines of the journal in question. If the rules are unclear, it is better to “overcommunicate” the tools used than to keep them quiet: specify exactly which program was used for what purpose (e.g., “the final version of the manuscript was checked using Paperpal”). This ensures transparency and avoids misunderstandings later on.

What does the future hold?

The use of artificial intelligence—whether for scientific purposes or in everyday life—is an emerging practice, and all signs indicate that this will remain the case for some time. AI integration in scientific publishing already goes beyond the simple question of whether or not it should be used—the future will likely be more about how to integrate these tools into research work in a responsible, transparent, and ethical manner.

The future of regulation will largely depend on what new AI tools emerge and how researchers use them. If there is a lot of abuse or misleading practices surrounding the use of AI, it is easy to imagine that publishers will tighten the current relatively flexible rules.

Although there are attempts at standardization—such as the recommendations of COPE and ICMJE—there is currently no global organization that has the same influence on all major publishers. However, smaller publishers are likely to follow the example of larger players, so some convergence is conceivable in the longer term.

That is why it is crucial for authors to stay up to date and follow the guidelines of journals in their field. If you need advice in this rapidly changing environment—whether you have a specific question about a journal’s guidelines or are simply unsure whether the use of a particular AI tool is ethical—feel free to contact us at authorsupport@lib.pte.hu, and we will be happy to help!